The ideas in this blog post and the main example comes from a book called “Mistakes Were Made (But Not By Me)” by Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson.

Consider these questions:

-

Have you ever tried to coach someone or help them operate more effectively, but they have been resistant to your guidance? What makes them so unwilling to be coached or helped?

-

Why are people so unwilling to admit that they have made a mistake?

-

Why are many organizational leaders unwilling to assess the effectiveness of their leadership and/or the morale of their employees?

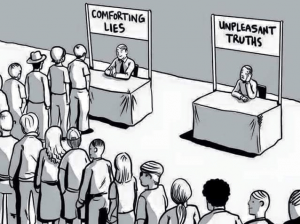

It all comes down to cognitive dissonance and self-justification.

Cognitive dissonance occurs whenever a person holds two cognitions (ideas, attitudes, beliefs, opinions) that are psychologically inconsistent.

An example of this would be someone that thinks smoking is bad, yet they smoke two packs a day.

We hate cognitive dissonance and we don’t rest until we find a way to reduce it. This requires us to self-justify.

Using the smoking example, that dissonance will drive the individual who smokes to either (1) stop smoking, or (2) convince themselves that smoking really is not harmful or that it has a number of other benefits that they cannot do without (e.g., reduce anxiety, prevents them from gaining weight).

It is cognitive dissonance, and its common partner, self-justification, that leads individuals to be unwilling to be coached, admit they have made a mistake, or unwilling to assess their effectiveness.

Ignaz Semmelweis

Let me give you a great example of this.

In the 1840s, hospitals in Vienna were facing a mysterious, terrifying epidemic of childbed (puerperal) fever, which was causing the deaths of about 15 percent of the women whose babies were being delivered by doctors. At the epidemic’s peak, one-third of the women in labor there died, three times the mortality rate of those attended by midwives. Then a Hungarian physician named Ignaz Semmelweis came up with a hypothesis to explain why so many women were dying of childbed fever: The doctors and medical students who were attending the women were going straight from doing autopsies on the women who had died the day before to the delivery rooms. Even though no one at the time knew about germs, Semmelweis thought they might be carrying a “morbid poison” on their hands. He instructed his students to wash their hands in a chlorine antiseptic solution before going to the maternity ward – and the women stopped dying.

These were astonishing, lifesaving results. Yet, when Semmelweis tried to teach other doctors about the value of washing their hands, they refused to accept the evidence, and essentially told him to “get lost.”

Here is Ignaz Semmelweis, giving his colleagues advice that will make them better doctors and help them save dozens, if not hundreds, of lives. This seems like a no-brainer.

So, why didn’t Semmelweis’s colleagues refuse to accept the evidence, and even thank him effusively for finding the reason for the tragic, unnecessary deaths of their patients?

Answer: Cognitive dissonance and self-justification.

In order for the physicians to accept his simple, lifesaving intervention, they would have to admit that they had been the cause of the deaths of all of those women in their care. This was an intolerable realization that went straight to the heart of the physicians’ view of themselves as medical experts and wise healers.

Stated differently, the doctors were unwilling to learn and become better doctors because their egos prevented them from acknowledging that, although they were likely doing their best, their ignorance and prior actions had led to the unnecessary deaths of many women.

So What?

This phenomenon is not unique to Vienna in the 1840’s. It happens all the time. Here are a couple recent examples where I have seen this:

Just today, I was putting together a survey for an organizational leader and he asked me to remove a question that would have directly revealed just how effective he was being as a leader. He justified the removal by citing that it was repetitious with other questions (it was similar, but definitely not repetitious). To me, it seemed he was fearful of what he might learn about himself.

Last week, a potential client was unwilling to accept the idea that her organization would benefit from focusing on developing and improving her employees’ mindsets despite the fact that research over three decades have demonstrated that mindsets are foundational to personal and organizational success. To me, it seemed like she was fearful of learning that she and many in her organization possessed negative mindsets.

In both of these instances, the individuals were rejecting information that is likely to improve and enhance their career and success.

This has led me to wonder:

-

What am I unwilling to see and learn because my ego is reluctant to admit that, despite my best intentions, I have not been operating as effectively as I could have, costing me time, money, and respect?

-

Am I willing to admit I have made mistakes?

-

Am I willing to admit that my thinking is not the best way to think?

-

Am I willing to embrace change, even though it may mean admitting that I have been heading in a less-than-ideal direction all along?

I hope this post causes you to ask and ponder similar questions.